Researcher and doctoral student Sweekrity Kanodia is working to overcome breast cancer by using open-source digital media to raise awareness of breast cancer and self-monitoring among women in rural villages in Nepal.

According to a scientific review published in 2018, “breast cancer is the second most common malignancy in Nepalese women. (...) In low-resource countries like Nepal, breast cancers are commonly diagnosed at late stages and women may receive inadequate treatment, pain relief or palliative care. Socio-economic disparities and insufficient financial resources hinder breast cancer prevention in Nepal.”(National Library of Medicine, 2018)

Aware of this, Sweekrity Kanodia, a FIRE doctoral student at the Planet Learning Institute, came up with the idea of creating a BreMo (Breast Health in Nepal Monitoring & Awareness) mobile app to help prevent and diagnose breast cancer in Nepal. An important part of her work is to find frugal and accessible solutions in the field of health.

Interview with a committed researcher.

Can you introduce yourself? What is your research project?

My name is Sweekrity Kanodia and I'm a lucky woman from a small village in Nepal who has had the opportunity to learn and grow. Growing up, I was very intrigued by biotechnology and the vastness of this field. As I delved deeper and deeper into this sea, I realized its potential to improve people's lives. Having experienced the difficulties of seeking medical care (I was often sick as a child) and observed the poverty around me, I wanted to develop frugal medical technologies.

That's why I joined the FIRE doctoral school's PhD program. As part of this program, I'm trying to defeat breast cancer with my team by harnessing digital means to educate women in rural villages in Nepal about breast cancer and self-monitoring.

My research project aims to improve breast health in Nepal using open and portable digital innovations. the 2 aspects of the project are:

- An open source application to educate women about breast health and breast cancer: it's a platform whose source code is easily accessible and can be modified or improved by anyone.

- 3D breast ghosts enabling women to learn how to distinguish fibroadenomas (normal growth) from cancerous cells during self-examination.

How far along is your project?

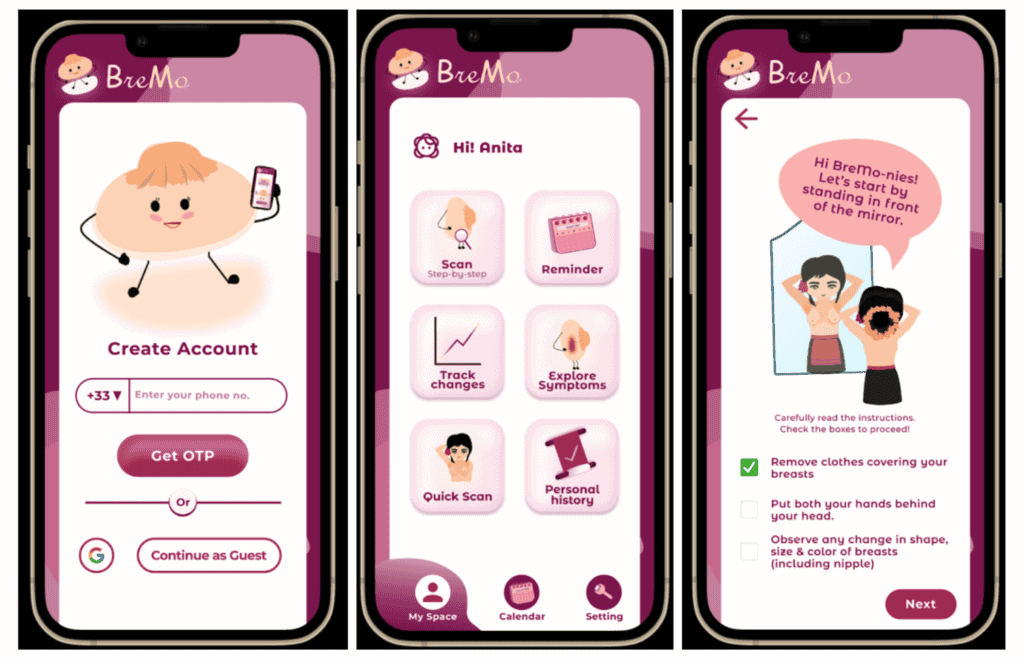

We're already working on the second version of the BreMo (Breast Health in Nepal Monitoring & Awareness) open source application, improving it based on feedback from a pilot study carried out at the Learning Planet Institute. We don't want to launch it just yet, as we first want to evaluate it scientifically by field-testing it with the target audience.

Logging into the BreMo application is very simple, and users can choose to log in as well. A simple interface allows users to move easily from one screen to another. Users can follow a step-by-step process to learn how to self-monitor and record their symptoms.

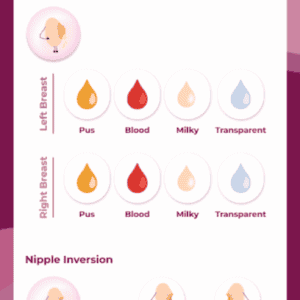

The main advantage of our BreMo application over other applications is that it allows users to select their symptoms from a list of symptoms, making them easier to identify and record.

As soon as this new version of BreMo is ready, we'll be ready to go out into the field - in the western regions of Nepal - to test our application against the traditional local method of disseminating information about breast cancer via posters.

I began collaborating with NGOs such as the Khokana Women's Society and the Nepal Network for Cancer Research and Treatment in Nepal to carry out field tests. We will bring together health volunteers from different districts and train them in BreMo.

This year, the International Women's Day is dedicated to “innovation and technology for gender equality”. Why did you decide to set up an app to raise awareness and share knowledge about breast cancer?

The rise of internet technologies and the rapid increase in the use of cell phones prompted me to think in this direction. I was surprised, during one of the camps in Nepal, to find the internet even in the most remote places. That's when I realized that with the mobile application, I could reach the most remote villages where healthcare infrastructures are scarce.

Open source technology is extremely important for spreading innovation worldwide. “Open source” means accessible to all, without individual rights. I'm in favor of open source or open science because all innovations and improvements in science and technology belong to everyone. Having rights and a monopoly on these innovations makes them less accessible and less affordable. If healthcare innovations become expensive, they will not be available to half the world's population living in poverty, which defeats the purpose of healthcare innovation and reform.

The open sharing of innovations such as portable ultrasound scanners will make it possible to reproduce the manufacture of these devices in Nepal without having to import them at unreasonable cost. The presence of such a device in every health post can enable women to visit health posts and examine their breasts once a month.

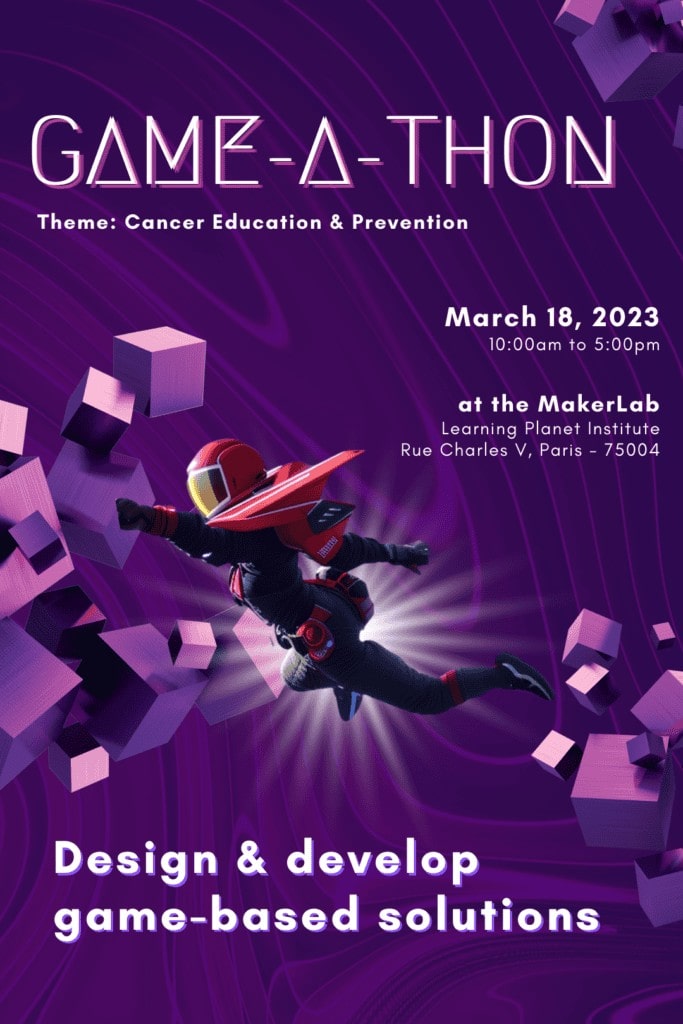

You're organizing a “game-a-thon” (a “game-hackathon”) March 18th. Can you tell us what it's all about in a few words?

Cancer is the world's leading cause of death. By 2020, 10 million people will die of cancer. There are around 100 types of cancer, and 30 to 50 % of these cancers can be prevented by avoiding risk factors and detecting cancers at an early stage. Disseminating knowledge about cancer is the first step in raising awareness, and therefore in early diagnosis.

I'm organizing a game-a-thon to promote cancer awareness and bring interested people together to discuss and develop different game ideas that can be used to promote information about different cancers.

People from all disciplines - with or without knowledge of game development - are invited to work in synergy and reproduce game-based solutions that can empower people to prevent the likelihood of contracting cancer, or improve their chances of survival by promoting early detection.

This approach is interesting because it allows people to discuss and imagine together. It also opens the way to diverse ideologies and thinking, leading to some crazy results!

NB: Registration closes on March 10, 2023.

Who do you work with on your research project, and how?

Fabien Reyal(Curie Institute) and Jean Christophe Thalabard(Université Paris Cité) as research supervisors.

I receive additional support from the Nepal Network For Cancer Research and Treatment to validate my ideas and work in the Nepalese context. Dr. Banira Karki, gynecologist and breast cancer awareness enthusiast, gives her advice on improving BreMo. The Khokana Women's Society helps me organize a training course for women community health volunteers (FCHV).

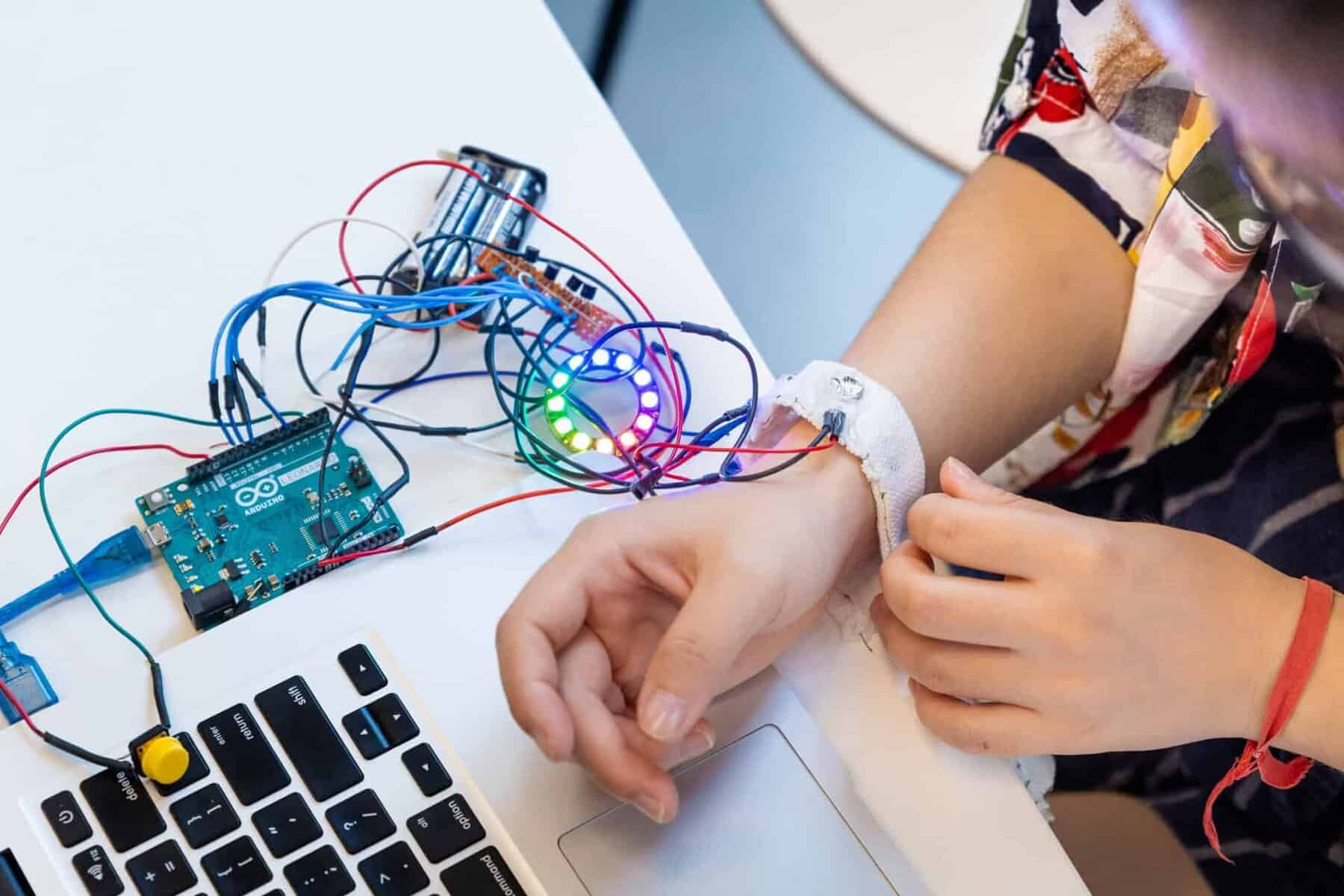

Dr Kevin Lhoste of MakerLab from the Learning Planet Institute, also helped me develop and test the application. 4 students from Learning Planet's Bachelor of Science program are now helping me to develop 3D breast phantoms that can be used for self-checking practice.

You are part of the’FIRE doctoral school, You work with the MakerLab, you work with FdV undergraduates on their student project (SCORE), you organize a game-a-thon... You're definitely an active part of the Learning Planet Institute ecosystem!

The Learning Planet Institute has been instrumental in helping me achieve my goals. The FIRE doctoral program has given me the opportunity to pursue my dream project and has provided me with exceptional support along the way. The Institute's MakerLab team and the support of excellent researchers and teachers help me to improve at every stage. The many seminars and workshops organized throughout the year help me to progress technically.

Read more :

- The March 18 event at MakerLab: here

Registration closes on March 10.

- FIRE doctoral school

Applications for this international, interdisciplinary doctoral program are now open! - Visit MakerLabA place for innovation, where frugal solutions to environmental and societal problems can be imagined, prototyped and manufactured.

- “Breast cancer in Nepal: Current status and future directions“, National Library of Medicine, 2018

This publication is part of the UNESCO Chair in the Science of Learning, established between UNESCO and Université Paris Cité, in partnership with the Learning Planet Institute.

The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization.