In the rapidly depopulating island town of Ikata, Japan, the classrooms are full. Professors are lecturing to students in suits, furiously scratching away at their notes as the blood-red sun recedes into a darkening sky. It's a Sunday afternoon, but this show would be the same on a Saturday or Monday.

Curiously, this teaching weekend constitutes an act of rebellion. The district recently mandated that teachers take at least one day off per week. The idea is that if teachers break with tradition by ceasing voluntary tutoring sessions on weekends, students could spend that time developing general interests and skills that aren't assessed through rigorous testing.

But, according to a local teacher, that's simply not the way things work. “The old way is the right way,” she asserts. “After all, why change what isn't broken?

This resistance to change is omnipresent in Japanese education. But it's not unique to the political arena, nor to Japan. Around the world, cases of resistance to change abound. In Brazil, private-sector efforts to introduce a renewable biofuel have been hampered by citizen fatigue with the associated land-use policies. In the USA, efforts to improve educational quality through the multi-billion dollar School Improvement Grants program have failed to deliver net learning gains - a disappointment often attributed to schools' reluctance to change their teaching practices in line with program guidelines.

It was against this backdrop that a unique Japanese concept was born. Known as shakaijissou (“social implementation”), it refers to the efforts made by government and civil society to put new ideas into practice.

At the Asia Pacific Initiative, a Japanese think tank, we interviewed dozens of creators, leaders and potential users of innovations about their experiences of social implementation. These conversations converged on the idea that supply-side logics are too often at the heart of resistance to change; innovators design new tools and policies based on assumptions about what citizens want, only to encounter their disinterest or inability to integrate this newness into their daily lives.

One of the solutions to this challenge is to stop focusing on constant creation and turn instead to the process of creating meaningful innovations that work in practice. Fundamentally, it's about generating the demand necessary for co-creation with citizens and, in so doing, developing responsive innovations that aren't resisted, but demanded.

But how can we empower a society that demands innovation? The demand for innovation is a cultivable social practice that relies on a diverse set of skills, knowledge and attitudes - the cognitive abilities to recognize gaps in current practices, for example, or an attitude of curiosity that stimulates the search for innovation. Based on this idea, we could design a progression of human capabilities required for such a demand.

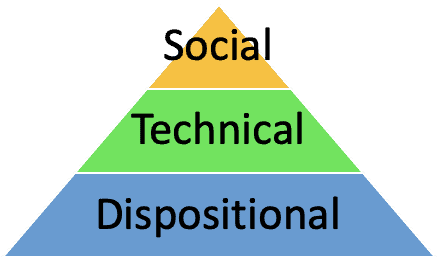

Over the past few months, I've been delving into the literature, from the learning sciences to marketing, to understand the design, implementation and adoption of innovation. The result is an additive and progressive model called the “adoption capability pyramid.”

At the base of the pyramid is a series of capabilities dispositional, These are the intrapersonal characteristics that drive people to seek out and adopt new practices and products. This stems from the recognition that the demand for innovation is a behavior, and that attitudes, inclinations and beliefs drive behavioral change. In line with decades of literature on the science of innovation, for example, a parent who values convention and routine might immediately reject a teacher's decision to educate his or her child using non-traditional, self-directed learning approaches, and would certainly not seek to collaborate on the design of new teaching techniques.

The skills techniques and the knowledge needed to recognize the value of an innovation and integrate it into everyday life are at the second level of the pyramid. These are the cognitive skills needed to identify how a new feature can solve an everyday problem, such as the pattern recognition skills needed to know when a new car-sharing platform can help a person save money or time compared to taking public transport. It's also about the skills and understanding needed to implement an innovation, in the same way that an educator may need a good knowledge of teaching and a range of learning skills to demand and implement a new pedagogical practice such as problem-based learning.

Since innovation can't succeed in isolation, the tip of the pyramid represents the tools we need to make it happen. social to disseminate a new idea in the social environment. Behavioral science has long argued that people are more likely to adopt a new idea or practice when their social network appreciates it. The ability to negotiate values, perceptions and meanings with one's community can therefore alternately hinder or accelerate innovation; on the positive side, for example, a person's communication skills and teamwork aptitude may enable them to discuss local challenges with a neighbor, negotiate the need for new waste disposal systems and rally support for a new plastics recycling service.

Preparing society for a rapidly changing world is easier said than done. Innovation tailored to society is hard to find, and buy-in is perhaps even harder. While only one piece of the social change puzzle, this pyramid could pave the way for leaders around the world to design educational opportunities that can empower a population demanding innovation. By preparing society to demand change, we move closer to a brighter, fairer future.

Fig. 1: Adoption capacity pyramid

Author:

Adam Barton is an educational researcher who studies global innovations that can help all learners thrive. He is particularly interested in participatory design, the definition and alignment of educational values, and the dynamics of social change.

He is currently a Visiting Fellow and Luce Scholar at the Asia Pacific Initiative, a Tokyo-based think tank, where he studies “social implementation” - harnessing community demand for change to design and implement sustainable social innovation. There, he studied and advised global policymakers on the potential of global innovations in education. He recently co-authored a book on the subject, Leapfrogging Inequality. Adam has worked extensively in Brazil, Bolivia and Washington, DC, as an English teacher, ethnographic researcher and director of educational programs.