In today's education systems around the world, we still often have, as Tom Hierck puts it, “21st century students, taught by 20th century adults, using 19th century pedagogy and tools, on an 18th century school calendar” These systems, like systems in general, often function to preserve the status quo, and are largely similar in design and operation to our past rather than our future. Although many inspiring and influential pedagogues and change-makers throughout the ages have enlightened us about how and why we learn, it has proved difficult to improve education, even though all stakeholders consider it necessary to do so in many areas.

We also live at a time when the effects of accelerated and complex change are having a profound impact on the world we live in, both globally and locally. The pressures created by certain dynamics, such as hyperconnection, developments in automation and industry, high-risk/high-potential technologies and threats of global collapse, are massive and need to be addressed urgently. In our increasingly automated and digital society, our unique human skills, such as creativity, empathy and adaptability, are becoming increasingly vital to our personal joy and well-being, as well as to a necessary and timely change in what might be required of us in our work. Yet these needs are not taken into account in most teaching and learning programs, let alone in “measures” of success in education, which are largely based on industrial, assembly-line learning.

Nevertheless, in the face of the entrenched dynamics of many educational systems, we are witnessing an increase in alternative learning approaches dedicated to methods of forecasting, exploration and anticipation. Mapping and spotting innovations have evolved towards a more holistic approach, taking into account the whole person, complex challenges and collaborative learning opportunities. These desires suggest a potential turning point for education systems, which need to move towards approaches that co-creatively shape our emerging future rather than operate from our past.

This article integrates the results of a global research project that shows that the evolution of education towards learning ecosystems is gaining momentum worldwide. Find out more about how this is happening around the world, Global Education Futures and SKOLKOVO School of Management asked me, Pavel Luksha and Joshua Cubista to co-author the forthcoming report “Learning Ecosystems: An emerging praxis for the future of education”. This research project interviewed 40 learning and education leaders from around the world who demonstrated a commitment to 1) intentionally integrating positive-impact learning solutions and/or experiences into educational practices, and 2) engaging and organizing in collaborative relationships with a diverse set of stakeholders, both inside and outside the education sector. The learning ecosystems studied in this project followed different types of dynamics, such as ecosystems that create conditions conducive to innovation and social or cultural development, to increasing fair and equitable opportunities in circumstances of gender, economic and ethnic inequality, and to regenerative economies in relation to the respective bioregional ecosystems, and also incorporated lessons from the Ecosystem Accelerator program in 10 regions of Russia.

What are learning ecosystems?

So, how do we embrace complexity and put it to work for us? Systems science suggests that ecosystems have a paradoxical ability to maintain both unity and variety for beneficial governance. Unity is established by creating shared interaction protocols and orienting all ecosystem participants towards cooperation, as well as establishing shared values and long-term goals. Variety is established through “evolutionary” protocols in the sense that there is no single blueprint for the ecosystem and any participant can engage in experimentation or exploration, and any participant can either achieve “evolutionary success” (begin to develop, grow, spread), or fail and “die out”.”

As a result of increasing complexity, connectivity and proximity, interconnections between different actors are growing, and this trend is giving rise to complex networks of knowledge production, but assembly-line learning and industry-inspired educational systems are not designed to evolve in response to the kind of growing complexities facing society today. We therefore need an “ecosystemic transition”, and we are indeed at the beginning of one, whereby we adopt the wisdom of regenerative living systems and model our relationships, interactions and organizational processes on the complex living adaptive systems on which all life depends. One indicator of this emerging transition is the growing use of the term “ecosystem” in a wide variety of sectors, from transportation and energy to healthcare, city administration, social innovation and the arts.

When we were asked to define learning ecosystems, our interviews with leaders around the world led to this emerging definition.

Learning ecosystems are networks of interconnected relationships that organize lifelong learning.

They are diverse, dynamic and evolving, linking learners and the community to foster individual and collective capabilities.

They have three objectives, dedicated to co-creating a prosperous future for people, places and our planet.

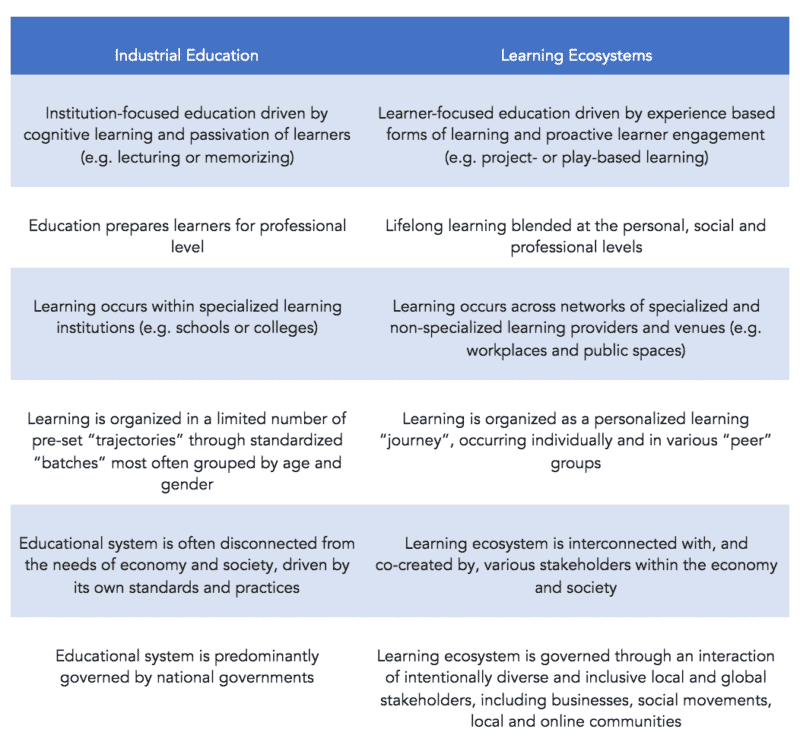

How does this differ from what might be considered the hallmark of most educational systems? The table below outlines some of the key differences our participants have noticed or co-created in the emergence of these systems.

Personal, local and global levels of a learning ecosystem

As you can see from the table above, learning ecosystems are particularly different from the education system, as they arise from and are guided at multiple levels by a complex network of objectives. Ecosystemists (leaders in this field) shared that the learning ecosystem seems to provide a multitude of objectives applicable at three different levels in order to integrate individual and collective needs. The interaction of personal, local and global is essential to establish the difference between previous approaches to education. The personal level focuses specifically on enhancing aspects such as individual growth and self-care, while the place level focuses on the development of the local community and learning opportunities within it, to be defined in context, and the planetary level focuses on our connection to the wider global needs of the world.

In terms of practical first steps, we've found that ecosystemists typically start with the local purpose of an ecosystem, primarily guided pragmatically by real needs, local challenges and identified opportunities rooted in local or regional context and history. Even if they don't know exactly what the outcome or response will be, they are determined and organized with the intention of understanding together, so that their impact becomes evident to all stakeholders in the process. The inherent motivations for organizing an ecosystem are as follows

- Immediate, location-based motivation. Working in an ecosystemic way will respond to the immediate local problem, to a profound need perceived by the community, industrial partners, the economy and the demands of the population. This need is infinitely rooted in the context and culture of a specific place.

- Global, planetary motivation. Interconnected with a broader planetary movement towards universal well-being on a global scale, ecosystem leaders see themselves as connected to part of a larger movement.

- Individual and personal motivation Their work is also innately linked to themselves and their development, and they want to organize learning and education for themselves so that they can live in the world in this way. Consequently, they recognize that they have to change and take care of their own well-being, just as they are part of the ecosystem in the same way as their project.

Conditions for learning ecosystems

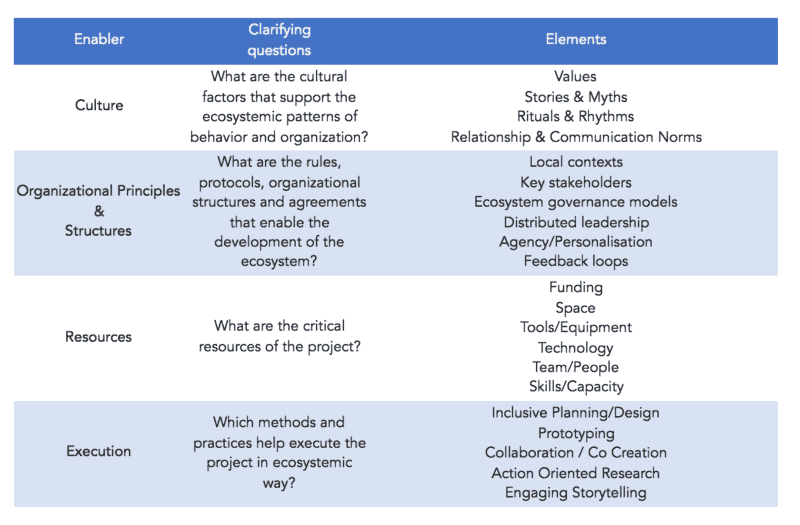

What makes learning ecosystems work? In the table below, I'll share the number of factors we've observed that support the transition or transformation to ecosystem modes of organization. These factors have been used to guide an ecosystem gas pedal program supporting the development of several Russian regions in their evolution.

If we know how to support them, why aren't we already organizing ourselves in an ecosystemic way? We have found that there are some notable and specific obstacles that frequently appear in projects, ranging from the relational to the structural. At the relational level in particular, it has often been said that, because of its emergent value, it can be difficult to free up time, space and impactful learning to develop the necessary skills, values and mindsets. Yet, when achieved, it is extremely compelling for participants and funders alike. Visit lack of confidence is the most frequently identified obstacle to ecosystem development. Vishal Talreja, founder of the non-profit organization Dream a Dream, based in India, pointed out, for example, that 'it's not recognized that we don't know how to work together. We assume we know how, but we don't invest enough time in the trust-building process”. These sentiments are confirmed by the views of educator Stephen Harris, former school principal and founder of Learnlife, who believes that the two main obstacles to learning ecosystems are linked to this relational element: “Firstly, teachers have never been taught emotional intelligence. Universities teach people to become agents of control within a group, to be supervised and controlled, which runs counter to a positive relationship. They need to learn how to have positive functional relationships, and these need to be in place before they move forward. Secondly, teachers have never been taught to collaborate. They think they can, but in fact they can't, which is not their fault, but they haven't been trained. Those who teach MBAs do so in collaborative teams, but we do the opposite in teaching. How can they become agents of change and collaborate if they can't do it themselves??

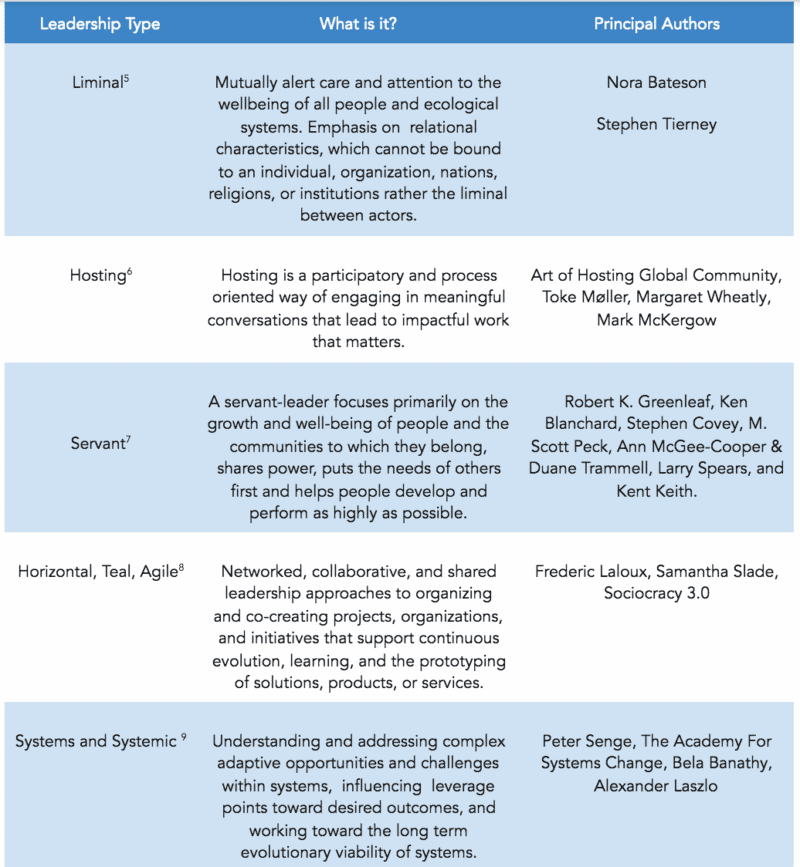

Ecosystem advocates spend a lot of time intentionally trying to develop these skills themselves, and supporting opportunities for authentic connection and vulnerability for them to do the same. It seems, then, that we need to reimagine and recreate ecosystem-level support for personal learning for development. This support must include educators and education stakeholders so that we can support those who lead education systems or initiatives to foster change for the benefit of others and the planet. An organization working at different levels to build and maintain networks of deep and useful relationships across the learning ecosystem is The Weaving Laboratory. Her work focuses on advancing the practice and profession of weaving learning ecosystems for universal well-being. This leadership development focuses on developing a different set of skills and ways of being than traditional leadership styles, and builds on the idea and importance of liminal leaders in today's world. It's an approach to leadership that relies less on hierarchical authority and centralized control, and more on organizing circles, facilitating conversations and building trusting relationships. It's about taking the lead, but also supporting others to step forward and take the lead, moving from ego to eco. The goal of weaving is a complex and nuanced discipline that involves guiding people from a wide range of institutions, roles, backgrounds and perspectives towards meaningful collaborations that have systemic impact.

Ecosystem thrivers: Leadership and learning

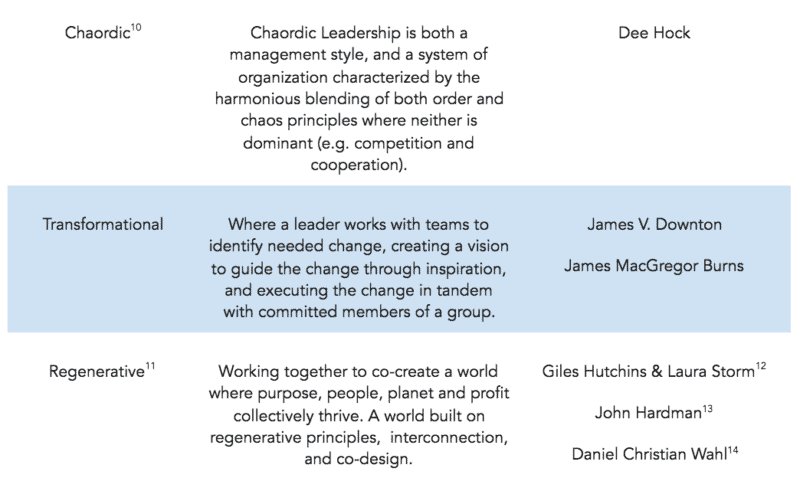

One might think that the difficulty of this type of organization might be the drawback, but those responsible for these projects and for education point out that the alternative of maintaining the status quo is not an option after all. So what are the roles and leadership needed to evolve learning ecosystems? Across the globe, there is a wide range of emerging leadership approaches that share commonalities in terms of impacting positive change locally and globally. The table below highlights some of the fundamental elements of evolving leadership approaches and some of the key people/communities shaping this change. It's the combination of these ways of working in learning ecosystems that makes us ” thriving ecosystems”, a position that requires you to wear many hats!

We are socialized to see what's wrong, what's missing, what's not right, to tear down other people's ideas and elevate our own. To some extent, our entire future may depend on learning to listen, to listen without assumptions or defenses.

- Adrienne Maree Brown, Emergent Strategy: Shaping change, changing the world

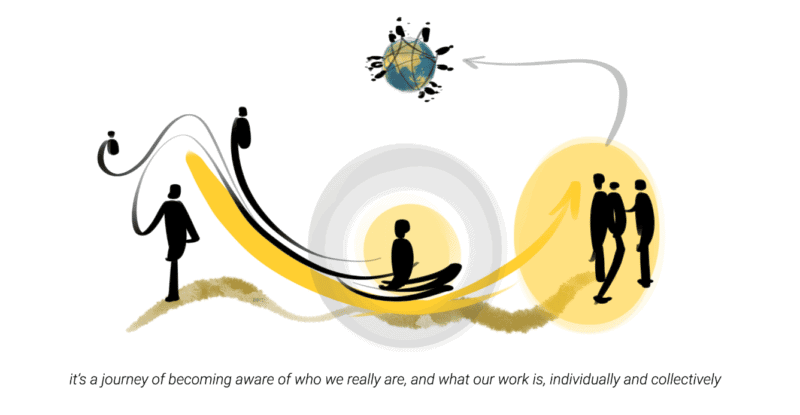

Many contributors to the research presented in this report also point to the pioneering approaches to learning and leadership development of The Presencing Institute as exemplary in the kind of individual and collective capacity-building needed to change the way we approach the challenges and opportunities we face in today's world. The Presencing Institute, for example, has developed a leadership program that “aims to activate the cofactors of a new global movement (and action research university) that integrates science, technology, consciousness and deep societal change to bridge the major ecological, social and spiritual divides of our time” Building on its fundamental theory of change, Theory U The Presencing Institute creates spaces for learners to “lead from the emerging future” and illuminates alternative paths we can take to evolve the way we learn together.

Credit: Image from Theory U.

Another way of understanding the work required to cultivate a thriving learning ecosystem is that of ecosystem gardening. Gardening, beyond the metaphor, is the practice of cultivating complex symbiotic living systems, and the work of cultivating learning ecosystems requires working with nature and her wisdom, learning from her, evolving our systems and evolving ourselves. According to Masanobu Fukuoka, “the ultimate goal of agriculture is not to cultivate crops, but to cultivate and perfect human beings” In this context, learning ecosystems are the “garden or farm” in which we cultivate healthy conditions for learning to flourish, both for individuals and for communities. This includes seeding opportunities, propagating projects, cultivating thriving ecosystems and cultivating our capacities as learners and leaders.

Thriving ecosystems garden to create new ways of learning and being in the world, both for themselves and for their local and/or global communities. This can take many forms such as tools, processes, events, gas pedals or art. They also often create technology platforms to connect this work and give visibility to change in the digital sphere so they can connect with more people and prove their impact to the community and funders. We see leaders using this language and talking about their work through the metaphor of gardening. Ismael Palacín, Director of the Fundació Jaume Bofill, The role of the ecosystem gardener is particularly visible outside the Euro-Atlantic world. In places like Western Europe or the USA, for example, there is a saturation of siloed and disconnected institutions and, in this context, the main role of an ecosystem leader is to connect and align, or weave links between the various players. However, in many parts of the world, such as Latin America, Africa, Russia or the Middle East, the institutional landscape is poorer, what some call “institutional voids”, and ecosystem leaders need to play a more proactive role in cultivating the landscape before activities such as weaving become a priority. An analogy can be made with the “rhythms of life”, the changing cycles of day and night and the changing seasons. Evolving projects and initiatives within an ecosystem, e.g. platforms, competitions, rankings and gas pedals, when introduced into a system, begin to influence the whole system. Here, an ecosystem gardener works with what is possible, guiding the evolution of an ecosystem towards more desirable outcomes.

Our emerging futures

In the words of Buckminster Fuller, “my general studies of global trends make it clear that nothing will be so surprising or abrupt in human history as the evolution of educational processes” We hope that the work of the people featured in this research will highlight the emerging praxis of learning ecosystems as a radical shift in the way we learn and lead together in the 21st century, advancing the evolution of education and learning. Each unique wave on the ocean is created by the coming together of swells, sometimes resulting from storms that occurred days before and thousands of kilometers away. While it can sometimes feel like ecosystem-based learning makes our work more complex and challenging, embracing complexity and future possibilities is actually a much more coherent way of navigating the complex dynamics before us. Learning ecosystems inspired by organic complex adaptive systems aim to offer learning pathways in line with the complexifying context of the 21st century. Creating learning ecosystems takes courage and endurance, it demands a lot from us and our communities, and it invites work that can span generations. The enthusiasm with which research participants shared their successes and failures in the ongoing work of co-creating learning ecosystems suggests to us that learning ecosystems can offer avenues of hope and possibility for the future of learning. It's up to us to co-create the future that lies ahead.

To find out more about learning ecosystems, real-life case studies and how you can work more ecosystemically, check out our forthcoming report published by Global Education Futures and SKOLKOVO School of Management “Learning Ecosystems: An emerging practice for the future of education”, written by myself, Pavel Luksha and Joshua Cubista. To find out more about my work on learning transformation and ecosystems, visit my website at’address www.jessicaspencerkeyse.com